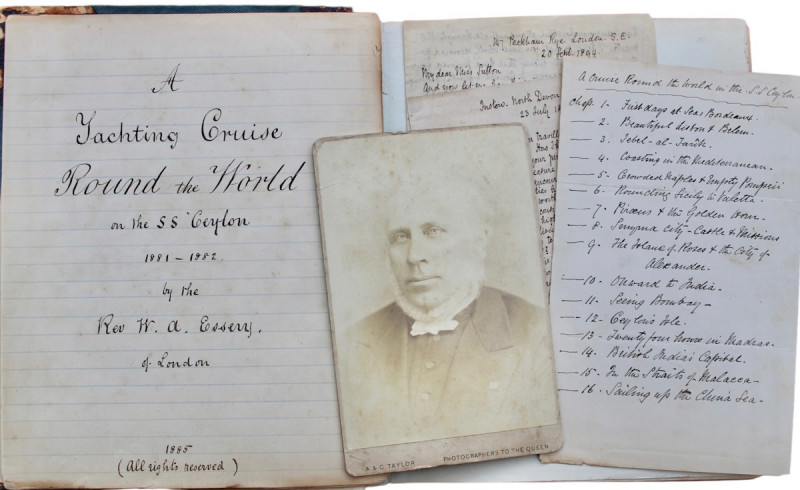

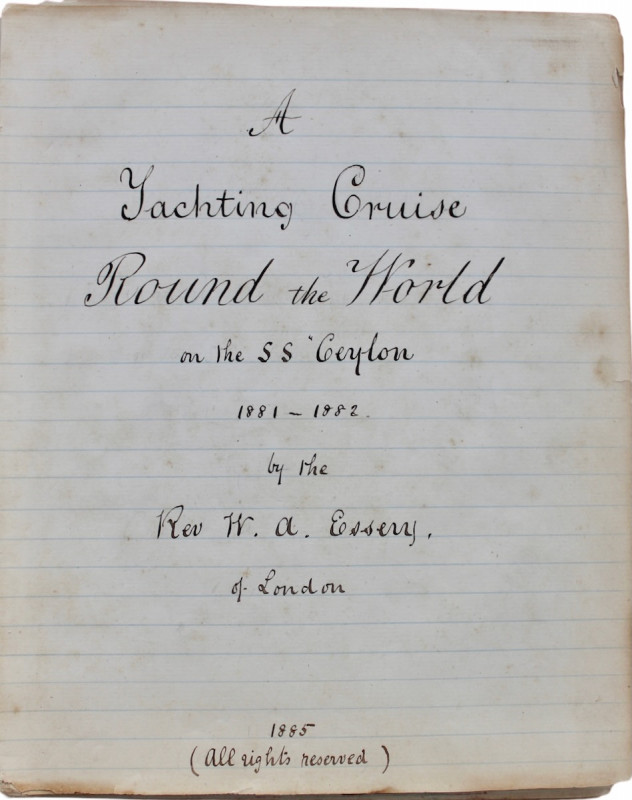

A Yachting Cruise Round the World on the SS Ceylon. 1881-2.

Book Description

THE FIRST COMMERCIAL WORLD CRUISE.

Rev. William Alfred ESSERY A Yachting Cruise Round the World on the SS Ceylon. 1881-2.

Manuscript, 1881 - [1885].

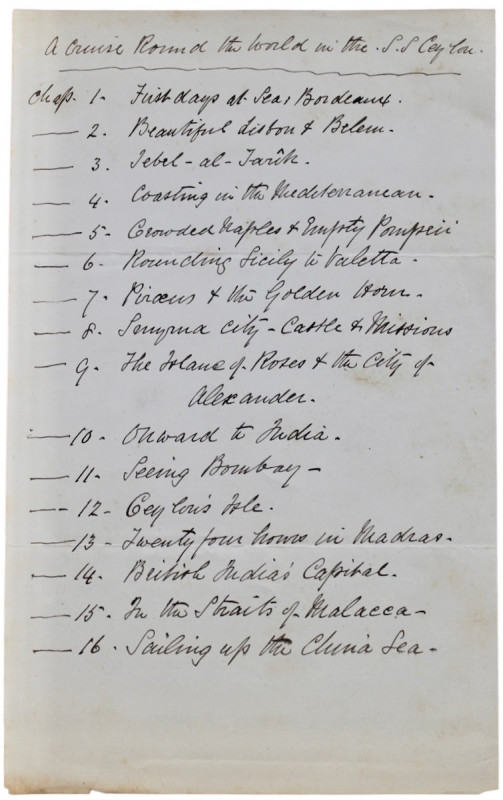

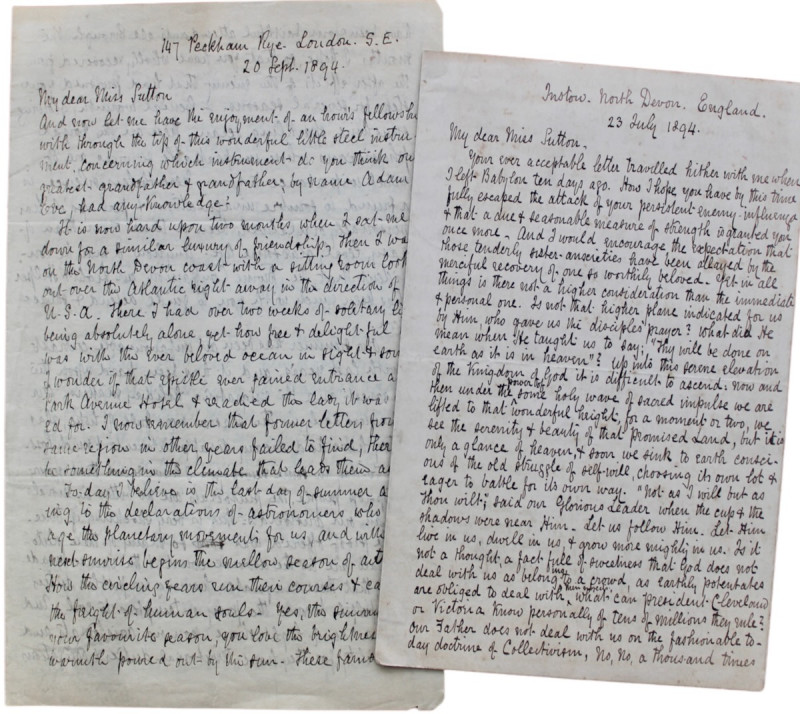

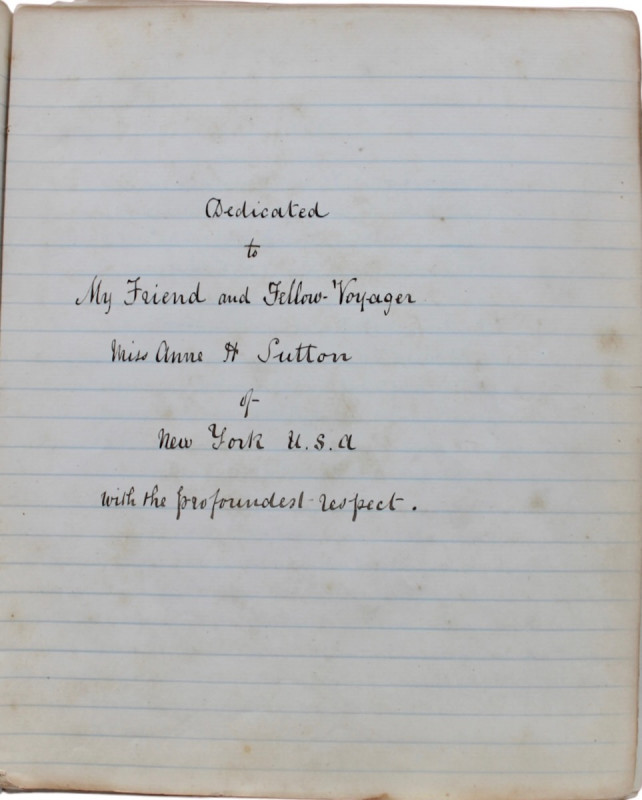

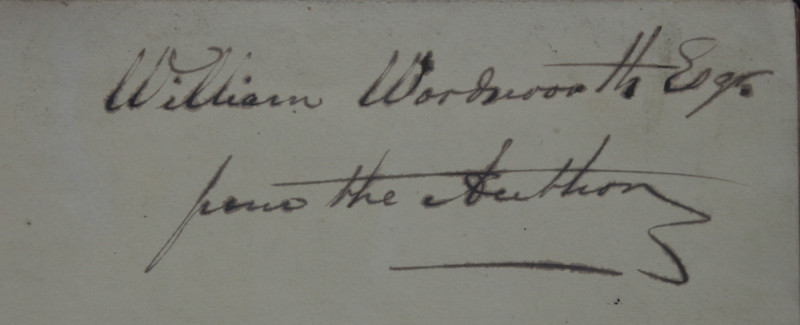

4to. pp. 280 numbered pages written on rectos only; 13 loosely inserted with title, dedication, preface and detailed contents. Also loosely inserted, abbreviated list of contents, two letters to the dedicatee, Miss Sutton of New York, a large cabinet portrait of the author inscribed verso from the author to Miss Sutton, dated October 1884.

A contemporary account of the voyage, with the loose supplementary pages added later when sent to Miss Sutton.

In his preface to the manuscript account of his cruise the Reverend Essery accepts that “there is now no novelty in a voyage round the world”. He is modest to a fault in his claims for his work: “it contains simply the record of the personal experience & observation of one who made the complete voyage from first to last.” He describes the limitations of the cruise: “we soon discovered serious inconvenience for abundant sight-seeing” but is proud that not only did they fail to “follow closely in the tracks of our distinguished predecessor,” namely Lady Brassey’s voyages in the Sunbeam, but in several respects outperformed the former; “out of a total of 77 ports & towns seen by us 41 had not been visited by the earlier party.” His aim in presenting the work to the public is equally modest, namely, to show “how universal is the distribution of beauty throughout the world.”

Dealer Notes

The Reverend’s journey begins on a disappointed note. His cabin, being the final booking, isn’t ready, there is no bed and his first night on board is both noisy and miserable. “Gloom hovered over us.” The atmosphere scarcely improves when, on the second night at sea, there is a cry of “man overboard”. Despite the best efforts of the crew, they are unable to recover “the unhappy man who had flung himself wildly into the sea.” After several days at sea, they arrive at Bordeaux on the feast of All Souls and encounter “shows of all sorts, dwarfs, monster women, performing monkeys and lions.” They proceed through the Bay of Biscay with the inevitable rough seas: “I tried to obtain some palliation to my misery by an application of the dull science of arithmetic…the endeavour cannot be esteemed a success.” As they round Cape Finisterre the weather worsens: “my cabin was a gulf of horrors” but things gradually improve to the extent that “I was able to perform that long neglected operation, a morning shave.” On 5th November they arrive at Lisbon and are impressed by its beauty whilst noting that “the women of the poor are worked outrageously hard, for you meet them continually barefoot, carrying crushing burdens on their heads.” As to Portuguese women in general: “Features not remarkable either way, the number I saw with a thin even line of hair on the upper lip was rather startling.”

They pass through the Mediterranean and after visiting Gibraltar follow the coast past Genoa before arriving at Naples: “What lively wretches these Neapolitans are.” The city itself is “the noisiest, dirtiest, cheeriest city of Europe.” Whilst there, they climb Vesuvius, “the spectacle of the crater was appalling, a giant furnace flamed before our eyes.” and then visit Pompeii: “A strange atmosphere of mystery pervades the place; in its deep silence you seem to hear the voices of the light hearted citizens who thronged the well worn pavements.” Their next stop is Palermo before continuing to Valetta where Essery is impressed by its sheer Britishness: “Malta has exceeded my expectations, it is so clean, lively, historic…British.”

Their next port of call is Constantinople, “the most cosmopolitan city in Europe.” Here they are struck by its sheer vitality: “”his ever wonderful conglomerate of humanity which no city in the world can match…the loveliest place out of paradise.” A paradise which ends with the passengers of the Ceylon fleeing a mass brawl in the bazaar as the traders come to blows over their custom!

On leaving Constantinople they cross the sea of Marmara and pass Troy, “the scene of Schliemann’s excavations” before reaching Smyrna. “As a port it is wonderfully prosperous & lively & merits the designation, the Liverpool of Asia Minor.” They explore the city with an armed escort and Essery is struck by “the number of huge jet black fellows”. He attends meetings with various missionaries and is told about the dangers they encounter. After several days at sea, they arrive at Alexandria. “All visitors are miserably tormented at the landing stage by donkey boys, beggars, touts, guides & the ragged loafers lying in wait there.” Essery is captivated by the sheer variety of merchants and traders: “Bedouins of the desert in thick blanket coats with cowls, Nubians in long white smocks, Copts with their mixed countenances, Turks with solemn aspect, Greeks & Jews with crafty, wily expressions & Franks in the best attire of London & Paris.” He describes such scenes with a journalist’s eye, lingering over incidentals of colour and form: “a sour looking old fellow squatting before a table, inkhorn, pens & paper ready waits to execute any epistle for the unlearned either of business, condolence, congratulations or love; at an open corner the cook is stooping down turning over his frizzling fish hoping to tempt the hungry passers”. He is dismissive of the modern city: “the glory of Alexandria is wholly in the past.”

On December 18th they enter Port Said before passing through the Suez Canal, “a work of human genius”. As they move through the Red Sea Essery describes Mahomet: “the false prophet of Arabia started first as a genuine Reformer but degenerated into a blood thirsty tyrant.” A few days later one of the passengers, a Miss Gammon, dies of cholera and is buried at sea. On January 4th they approach Bombay, “a prospect of novel beauty embosomed in a profuse tropical vegetation.” The city itself “made a small forest of tall & sooty chimneys, of cotton mills & other factories” giving “a peculiarly English look…reminding me of the Chatham dockyards.” Once again it is the people who most interest Essery: “I found Parsees clad in white, wearing the glazed, oval, sloping hat characteristic of the race…. a wonderfully bright & intelligently looking lot of men with superior aptitudes for all commercial transactions.” He is taken on a tour of Bombay by an English colleague: “the thoroughfares are magnificent, the public buildings most imposing.” They visit a Parsee cemetery where the bodies are placed on towers “where they are wholly devoured by vultures.” And then a school where the children “were stirred with no slight commotion” on witnessing a party of white men. They are refused entry to a Buddhist temple and the Brahmin challenges their faith: “he could not understand how Jesus could be God.” In the evening they return to the bazaar: “Throngs of men semi-nude & clad in white press everywhere” before visiting a Jain animal hospital, their central belief being “not to kill nor injure life in any form.” On the second day he visits the island of Elephanta and its famous caves: “The stupendous elevation is hewn out of rock” but is determined not to be impressed by its marvellous carvings: “I looked round with a saddened spirit on the desolate symbols of man’s blindness & idolatry.” Presumably the wrong kind of idolatry. Their stay at Bombay ends with another tour “of the fine city of Bombay.”

On the following day they proceed to Ceylon, visiting Kandy, “the ancient capital” and then Colombo, hugely impressed by the countryside: “Luxuriance is the predominant feature of this ever dissolving landscape, as it changes from nice terraces to palm forests, coffee tree plantations & tea growing gardens.” From Ceylon they travel to Madras during which “the heat seemed possessed of a murderous intent.” Madras itself is a disappointment, “the most unpicturesque city in the world.” All around the city can be seen “numerous charms, contrivances to avert the evil eye” due to the fact that “the Hindus must be most hearty believers in the doctrine of the universal depravity of man.” For the first time on the voyage Essery talks of the poverty of the local people: “so cheap a commodity is human labour in India.” He visits a Hindu shrine and once again his Christian prejudices prevent him from fully appreciating its beauty: “a pitying sadness fell upon me as I looked at these grotesque & venerated idols that had received the homage of many unenlightened generations.”

Their next stop is British India’s Capital – Calcutta. They begin with the Maidan, “the Hyde Park of the Indian metropolis…a large verdant plain nearly two miles long and one broad.” before visiting Fort William, “the largest & most perfect in India, constructed by Lord Clive.” They finish the first day in the Botanical Gardens, “the most beautiful park of Calcutta…a vast circular cathedral.” On the following day Essery goes to the banks of the Ganges “where the natives perform their ablutions.” He is horrified by the fact that “the water is full of mud & thick with filth yet the worshippers are seen drinking the fluid.” His verdict on a group of Fakirs is equally harsh and without any sense of irony: “these degraded samples of demented heathen saints could not but excite shame, pity & sorrow.” On the whole “Calcutta is something of a disappointment to me…Bombay is a queenly city by the side of Calcutta & yields the passing traveller far more delight.”

On the 3rd of Feb. they arrive at Penang, “a pretty place both on land & water. Few oriental ports offer a more pleasing scene.” Essery is particularly impressed with Singapore which “Justifies all that has been written of its loveliness.” On arrival they are invited to a reception by the Maharajah of Johore from whom “Singapore was purchased (from) sixty years ago.” The contrast is noteworthy: “then it had but 150 miserable Malay fisherman as its population but is now the fourth European city of India.” Once ashore they visit the obligatory temple and watch various ceremonies which fail again to meet with the devout Essery’s Christian approval. Their religious practices were all “gaudy, dirty & repulsive.” After the ceremony they visit the Raffles Museum. Next day they meet the Maharajah: “his figure was rotund, his complexion very dark, his face shaven excepting the moustache, his countenance was exceedingly good natured & English looking.” The banquet is lavish, the food copious, “seventy people in all sat down..there were sixteen courses & wines were served in lavish abundance.” A constant throughout their time in Singapore is the rain, “the annual rainfall measures eight and a half feet.”

Their journey up the China Sea is thoroughly miserable due to high winds and a rolling sea and they are greatly relieved when, on 17th Feb. they reach Manila. “The streets are broad, free from open drains & paraded by a population more abundantly attired than the dark copper coloured throngs we had so lately been associating with.” Spanish influence is predominant and the churches catholic; Protestant churches are not allowed: “Catholics here are Inquisition Catholics & would tear down any protestant place of worship immediately.” Essery concludes: “this must be the most intolerant bit of territory on the earth.” The cathedral, as well as the many churches they visit, are all recent, “due to the terrible convulsion of nineteen years ago.” Despite his aversion to Catholicism Essery is impressed by Spanish rule: “everybody seemed to be at work, all the people looked in good condition, well fed, well clothed, the dealers were independent & did not show the eagerness of the Hindu & Cingalese for the cash we offered for their goods.”

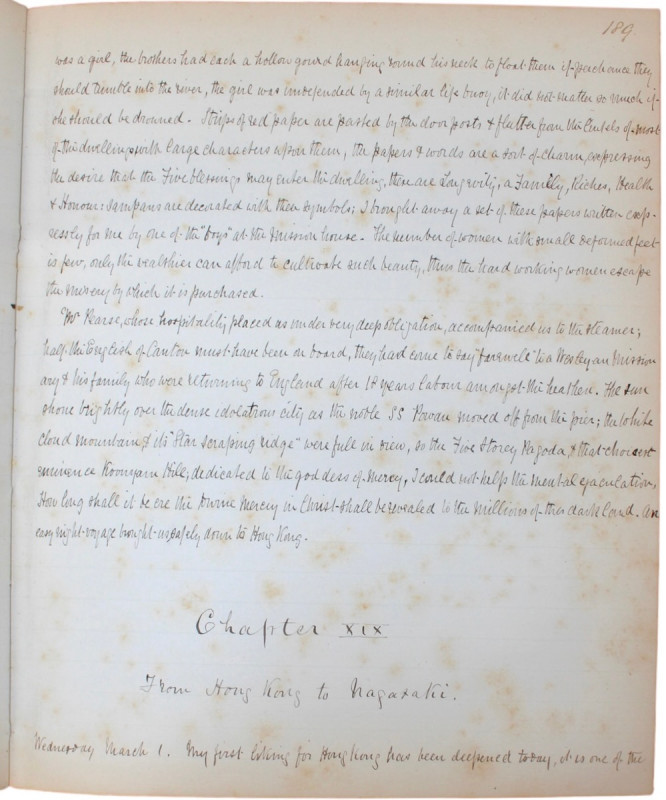

Hong Kong, “the island of Fragrant Streams”, enchants the visitors: “The beauty of the scene exceeded our expectations greatly.” Essery notes similarity of dress in both men and women and an equality in their relationships not present elsewhere. They first visit Canton and are struck by the teeming crowds: “what a dense herd of humanity we plunged into.” They escape into “the Concession where foreigners reside…a guard keeps the gate of entrance & no native is allowed to pass it.” On an evening walk through the streets of the colony they are met with “the incessant noise of exploding crackers, the Chinese method for driving away evil demons.” Passing through the dense, colourful streets they are greeted by cries of “Foreign devils”, this rising to a crescendo as they approach the “noted temple of 500 genii, or Flowery Forest Monastery.” Founded in 503 A.D. it is “one of the wealthiest religious buildings in Canton.” The following morning Essery and his friend Green tour “the vast city of Canton”, carried on three chairs by nine bearers, the only form of transport throughout the city. The names of the streets, “though reeking with atrocious effluvia” are colourful: “Refreshing Breezes Street, market of Golden Profits and New Green Pea Street”. They pass through “one of the most vast & wonderful bazaars of merchandize in the world.” They move quickly on “as pocket picking is one of the native accomplishments.” He then visits a Confucian temple which proves something of a disappointment, causing him to remark “Confucianism is no popular religion for the multitude, it is rather a system for the ruling & learned class.” In conversation with their guide Essery is told that the guide has three wives. The first two failed to produce a son, “for every Chinaman must have a son.” He goes on to explain: “poor man can sell pretty daughters to rich man for wife, and rich man can buy as many as he like for his money.” The visit continues with the temple of Horrors, followed by a tour of the prison where they witness “a man being sawn asunder, another bastinadoed.” They finish with a walk along the city walls to the Emperor’s temple whereupon Essery expresses his views on the Chinese character: “what a deathlike stagnation reigns over the civilisation of this great land, there is no intellectual growth…. they hate foreigners with a perfect hatred & count them an utter abomination.” As they leave Hong Kong Essery confesses “it is one of the most charming places in the East.”

On the 10th March they arrive at the recently opened port of Nagasaki. “All the coast scenery indicated the presence of a thrifty, industrious population….signs of prosperity greeted the eye.” As is his custom Essery provides a detailed and perceptive description of his surroundings: “Nagasaki certainly has a physiognomy of its own…The streets are wide comparatively…There is no bustle in the thoroughfares.” What particularly amuses him is the diminutive nature of the city: “Everything is so lilliputian that you feel like walking through a doll’s city.” The women in particular are “short, chubby, broad flat faced, rosy cheeked.” After Nagasaki, Essery visits the imperial quarter and palace of Kioto with its “famous lilliputian gardens.””The next day he visits several Buddhist temples; Kinkakuji Temple (Golden Pavilion), “the most magnificent in all Kioto” as well as Toji and Nanzenji temples. On the following morning he sets off for Osaka and visits the Castle, “the most astonishing architectural work in Japan.”

On the 26th March they leave Japan and head for Honolulu, a journey of fifteen days. They arrive after several days of mountainous seas to find that Honolulu “carries a thoroughly American look with its one storied buildings of red wood.” The Japanese ambassador joins the Ceylon and they leave for San Francisco. On arrival, Essery follows his normal routine of exploring the city and meeting people: “We were astonished at the use of timber for everything, the broad street is only a floor of thick, transparent planks.” Although the city is of little interest he is impressed by the countryside: “the Santa Clara valley is confessedly one of the most fertile & beautiful regions of queenly California.” He finds Americans particularly friendly; they have “a pleasant autobiographical style of speech even with the passing stranger.” As a city of emigrants San Francisco is divided into quarters: “Irish, French, Chinese & Aristocratic.” Many of the passengers leave the Ceylon at San Francisco, “nineteen only continuing the cruise” after which the Ceylon sets off for South America.

Lima is their next stop. “The gentlemen are like those at home, with European clothing, the ladies offer more variety, attired as middle class French ladies would be in Paris.” The Plaza Mayor impresses, “so rich in historical associations.” It is a public holiday and everywhere is crowded, “one thing struck me, the easy indifference of the conquered people.” The scenery around Lima is “desolate, the refuse heaps & neglected lands are given up to thousands of filthy vultures.” The recent war with Chile dominates conversation: “The Chilian soldiers were so maddened by their work of slaughter that they killed on & on in sheer wantonness.” They visit Chorillos, “the Brighton of Peru” and find that the town “was bombarded, captured & utterly destroyed in January 1881.” And even now “the town was like a place shaken to the earth by an earthquake…property wrecked, people slaughtered, huge misery endured.” They move on to Valparaiso, “a prosperous, wealthy place full of activity” before setting off to the foothills of the Andes: “we were carried over gorges, underneath frightful masses of rock & through pasture land,” before arriving at “the amphitheatre of hills engirdling Santiago.” The next morning, they visit the square of the Campania “where, in 1863, nearly 2000 victims perished in flames by a most agonizing death.”

On June 19th the Ceylon passes through the Straits of Magellan but the atrocious weather prevents them from landing at the Falkland Islands. Instead, they proceed to Montevideo. First impressions are favourable: “all the leading streets of the city are well built & even handsome, especially the Calle 18th des Julio. The two most delicious things of Montevideo are the climate & the flowers.” July 15th sees our party in Rio de Janeiro where they witness one of the many festivals complete with fireworks. After a brief visit the next stop is El Salvador where they visit the market, “a splendid spot for the study of niggerhood with all its farcical clothing, grimaces, antics & jokes.”

The journey across the tropics homeward is uneventful and on August 10th they arrive in Tenerife. “It was unspeakably joyful after 15 days incarceration to leap ashore on the pretty pier & ramble about the quiet, clean, sunny little town.” On the way back to England Essery lists, in true Victorian fashion, the achievements of their epic cruise around the world: “we stopped at 43 ports & we visited 34 inland cities & towns…I find further that we have seen 41 places not touched by Lady Brassey’s expedition…. I learn our whole cruise will measure 38,217 nautic miles.” With this great achievement, presented to the reader with a characteristic flourish, the redoubtable Reverend Essery brings to a close his journal, as epic in its scale as the journey he has both endured and at times enjoyed. The final sentence of the journal reflects his irrepressible good humour: “Our first business is to hurry on shore & flash by electricity to dear friends the message “Arrived, all well.””

They pass through the Mediterranean and after visiting Gibraltar follow the coast past Genoa before arriving at Naples: “What lively wretches these Neapolitans are.” The city itself is “the noisiest, dirtiest, cheeriest city of Europe.” Whilst there, they climb Vesuvius, “the spectacle of the crater was appalling, a giant furnace flamed before our eyes.” and then visit Pompeii: “A strange atmosphere of mystery pervades the place; in its deep silence you seem to hear the voices of the light hearted citizens who thronged the well worn pavements.” Their next stop is Palermo before continuing to Valetta where Essery is impressed by its sheer Britishness: “Malta has exceeded my expectations, it is so clean, lively, historic…British.”

Their next port of call is Constantinople, “the most cosmopolitan city in Europe.” Here they are struck by its sheer vitality: “”his ever wonderful conglomerate of humanity which no city in the world can match…the loveliest place out of paradise.” A paradise which ends with the passengers of the Ceylon fleeing a mass brawl in the bazaar as the traders come to blows over their custom!

On leaving Constantinople they cross the sea of Marmara and pass Troy, “the scene of Schliemann’s excavations” before reaching Smyrna. “As a port it is wonderfully prosperous & lively & merits the designation, the Liverpool of Asia Minor.” They explore the city with an armed escort and Essery is struck by “the number of huge jet black fellows”. He attends meetings with various missionaries and is told about the dangers they encounter. After several days at sea, they arrive at Alexandria. “All visitors are miserably tormented at the landing stage by donkey boys, beggars, touts, guides & the ragged loafers lying in wait there.” Essery is captivated by the sheer variety of merchants and traders: “Bedouins of the desert in thick blanket coats with cowls, Nubians in long white smocks, Copts with their mixed countenances, Turks with solemn aspect, Greeks & Jews with crafty, wily expressions & Franks in the best attire of London & Paris.” He describes such scenes with a journalist’s eye, lingering over incidentals of colour and form: “a sour looking old fellow squatting before a table, inkhorn, pens & paper ready waits to execute any epistle for the unlearned either of business, condolence, congratulations or love; at an open corner the cook is stooping down turning over his frizzling fish hoping to tempt the hungry passers”. He is dismissive of the modern city: “the glory of Alexandria is wholly in the past.”

On December 18th they enter Port Said before passing through the Suez Canal, “a work of human genius”. As they move through the Red Sea Essery describes Mahomet: “the false prophet of Arabia started first as a genuine Reformer but degenerated into a blood thirsty tyrant.” A few days later one of the passengers, a Miss Gammon, dies of cholera and is buried at sea. On January 4th they approach Bombay, “a prospect of novel beauty embosomed in a profuse tropical vegetation.” The city itself “made a small forest of tall & sooty chimneys, of cotton mills & other factories” giving “a peculiarly English look…reminding me of the Chatham dockyards.” Once again it is the people who most interest Essery: “I found Parsees clad in white, wearing the glazed, oval, sloping hat characteristic of the race…. a wonderfully bright & intelligently looking lot of men with superior aptitudes for all commercial transactions.” He is taken on a tour of Bombay by an English colleague: “the thoroughfares are magnificent, the public buildings most imposing.” They visit a Parsee cemetery where the bodies are placed on towers “where they are wholly devoured by vultures.” And then a school where the children “were stirred with no slight commotion” on witnessing a party of white men. They are refused entry to a Buddhist temple and the Brahmin challenges their faith: “he could not understand how Jesus could be God.” In the evening they return to the bazaar: “Throngs of men semi-nude & clad in white press everywhere” before visiting a Jain animal hospital, their central belief being “not to kill nor injure life in any form.” On the second day he visits the island of Elephanta and its famous caves: “The stupendous elevation is hewn out of rock” but is determined not to be impressed by its marvellous carvings: “I looked round with a saddened spirit on the desolate symbols of man’s blindness & idolatry.” Presumably the wrong kind of idolatry. Their stay at Bombay ends with another tour “of the fine city of Bombay.”

On the following day they proceed to Ceylon, visiting Kandy, “the ancient capital” and then Colombo, hugely impressed by the countryside: “Luxuriance is the predominant feature of this ever dissolving landscape, as it changes from nice terraces to palm forests, coffee tree plantations & tea growing gardens.” From Ceylon they travel to Madras during which “the heat seemed possessed of a murderous intent.” Madras itself is a disappointment, “the most unpicturesque city in the world.” All around the city can be seen “numerous charms, contrivances to avert the evil eye” due to the fact that “the Hindus must be most hearty believers in the doctrine of the universal depravity of man.” For the first time on the voyage Essery talks of the poverty of the local people: “so cheap a commodity is human labour in India.” He visits a Hindu shrine and once again his Christian prejudices prevent him from fully appreciating its beauty: “a pitying sadness fell upon me as I looked at these grotesque & venerated idols that had received the homage of many unenlightened generations.”

Their next stop is British India’s Capital – Calcutta. They begin with the Maidan, “the Hyde Park of the Indian metropolis…a large verdant plain nearly two miles long and one broad.” before visiting Fort William, “the largest & most perfect in India, constructed by Lord Clive.” They finish the first day in the Botanical Gardens, “the most beautiful park of Calcutta…a vast circular cathedral.” On the following day Essery goes to the banks of the Ganges “where the natives perform their ablutions.” He is horrified by the fact that “the water is full of mud & thick with filth yet the worshippers are seen drinking the fluid.” His verdict on a group of Fakirs is equally harsh and without any sense of irony: “these degraded samples of demented heathen saints could not but excite shame, pity & sorrow.” On the whole “Calcutta is something of a disappointment to me…Bombay is a queenly city by the side of Calcutta & yields the passing traveller far more delight.”

On the 3rd of Feb. they arrive at Penang, “a pretty place both on land & water. Few oriental ports offer a more pleasing scene.” Essery is particularly impressed with Singapore which “Justifies all that has been written of its loveliness.” On arrival they are invited to a reception by the Maharajah of Johore from whom “Singapore was purchased (from) sixty years ago.” The contrast is noteworthy: “then it had but 150 miserable Malay fisherman as its population but is now the fourth European city of India.” Once ashore they visit the obligatory temple and watch various ceremonies which fail again to meet with the devout Essery’s Christian approval. Their religious practices were all “gaudy, dirty & repulsive.” After the ceremony they visit the Raffles Museum. Next day they meet the Maharajah: “his figure was rotund, his complexion very dark, his face shaven excepting the moustache, his countenance was exceedingly good natured & English looking.” The banquet is lavish, the food copious, “seventy people in all sat down..there were sixteen courses & wines were served in lavish abundance.” A constant throughout their time in Singapore is the rain, “the annual rainfall measures eight and a half feet.”

Their journey up the China Sea is thoroughly miserable due to high winds and a rolling sea and they are greatly relieved when, on 17th Feb. they reach Manila. “The streets are broad, free from open drains & paraded by a population more abundantly attired than the dark copper coloured throngs we had so lately been associating with.” Spanish influence is predominant and the churches catholic; Protestant churches are not allowed: “Catholics here are Inquisition Catholics & would tear down any protestant place of worship immediately.” Essery concludes: “this must be the most intolerant bit of territory on the earth.” The cathedral, as well as the many churches they visit, are all recent, “due to the terrible convulsion of nineteen years ago.” Despite his aversion to Catholicism Essery is impressed by Spanish rule: “everybody seemed to be at work, all the people looked in good condition, well fed, well clothed, the dealers were independent & did not show the eagerness of the Hindu & Cingalese for the cash we offered for their goods.”

Hong Kong, “the island of Fragrant Streams”, enchants the visitors: “The beauty of the scene exceeded our expectations greatly.” Essery notes similarity of dress in both men and women and an equality in their relationships not present elsewhere. They first visit Canton and are struck by the teeming crowds: “what a dense herd of humanity we plunged into.” They escape into “the Concession where foreigners reside…a guard keeps the gate of entrance & no native is allowed to pass it.” On an evening walk through the streets of the colony they are met with “the incessant noise of exploding crackers, the Chinese method for driving away evil demons.” Passing through the dense, colourful streets they are greeted by cries of “Foreign devils”, this rising to a crescendo as they approach the “noted temple of 500 genii, or Flowery Forest Monastery.” Founded in 503 A.D. it is “one of the wealthiest religious buildings in Canton.” The following morning Essery and his friend Green tour “the vast city of Canton”, carried on three chairs by nine bearers, the only form of transport throughout the city. The names of the streets, “though reeking with atrocious effluvia” are colourful: “Refreshing Breezes Street, market of Golden Profits and New Green Pea Street”. They pass through “one of the most vast & wonderful bazaars of merchandize in the world.” They move quickly on “as pocket picking is one of the native accomplishments.” He then visits a Confucian temple which proves something of a disappointment, causing him to remark “Confucianism is no popular religion for the multitude, it is rather a system for the ruling & learned class.” In conversation with their guide Essery is told that the guide has three wives. The first two failed to produce a son, “for every Chinaman must have a son.” He goes on to explain: “poor man can sell pretty daughters to rich man for wife, and rich man can buy as many as he like for his money.” The visit continues with the temple of Horrors, followed by a tour of the prison where they witness “a man being sawn asunder, another bastinadoed.” They finish with a walk along the city walls to the Emperor’s temple whereupon Essery expresses his views on the Chinese character: “what a deathlike stagnation reigns over the civilisation of this great land, there is no intellectual growth…. they hate foreigners with a perfect hatred & count them an utter abomination.” As they leave Hong Kong Essery confesses “it is one of the most charming places in the East.”

On the 10th March they arrive at the recently opened port of Nagasaki. “All the coast scenery indicated the presence of a thrifty, industrious population….signs of prosperity greeted the eye.” As is his custom Essery provides a detailed and perceptive description of his surroundings: “Nagasaki certainly has a physiognomy of its own…The streets are wide comparatively…There is no bustle in the thoroughfares.” What particularly amuses him is the diminutive nature of the city: “Everything is so lilliputian that you feel like walking through a doll’s city.” The women in particular are “short, chubby, broad flat faced, rosy cheeked.” After Nagasaki, Essery visits the imperial quarter and palace of Kioto with its “famous lilliputian gardens.””The next day he visits several Buddhist temples; Kinkakuji Temple (Golden Pavilion), “the most magnificent in all Kioto” as well as Toji and Nanzenji temples. On the following morning he sets off for Osaka and visits the Castle, “the most astonishing architectural work in Japan.”

On the 26th March they leave Japan and head for Honolulu, a journey of fifteen days. They arrive after several days of mountainous seas to find that Honolulu “carries a thoroughly American look with its one storied buildings of red wood.” The Japanese ambassador joins the Ceylon and they leave for San Francisco. On arrival, Essery follows his normal routine of exploring the city and meeting people: “We were astonished at the use of timber for everything, the broad street is only a floor of thick, transparent planks.” Although the city is of little interest he is impressed by the countryside: “the Santa Clara valley is confessedly one of the most fertile & beautiful regions of queenly California.” He finds Americans particularly friendly; they have “a pleasant autobiographical style of speech even with the passing stranger.” As a city of emigrants San Francisco is divided into quarters: “Irish, French, Chinese & Aristocratic.” Many of the passengers leave the Ceylon at San Francisco, “nineteen only continuing the cruise” after which the Ceylon sets off for South America.

Lima is their next stop. “The gentlemen are like those at home, with European clothing, the ladies offer more variety, attired as middle class French ladies would be in Paris.” The Plaza Mayor impresses, “so rich in historical associations.” It is a public holiday and everywhere is crowded, “one thing struck me, the easy indifference of the conquered people.” The scenery around Lima is “desolate, the refuse heaps & neglected lands are given up to thousands of filthy vultures.” The recent war with Chile dominates conversation: “The Chilian soldiers were so maddened by their work of slaughter that they killed on & on in sheer wantonness.” They visit Chorillos, “the Brighton of Peru” and find that the town “was bombarded, captured & utterly destroyed in January 1881.” And even now “the town was like a place shaken to the earth by an earthquake…property wrecked, people slaughtered, huge misery endured.” They move on to Valparaiso, “a prosperous, wealthy place full of activity” before setting off to the foothills of the Andes: “we were carried over gorges, underneath frightful masses of rock & through pasture land,” before arriving at “the amphitheatre of hills engirdling Santiago.” The next morning, they visit the square of the Campania “where, in 1863, nearly 2000 victims perished in flames by a most agonizing death.”

On June 19th the Ceylon passes through the Straits of Magellan but the atrocious weather prevents them from landing at the Falkland Islands. Instead, they proceed to Montevideo. First impressions are favourable: “all the leading streets of the city are well built & even handsome, especially the Calle 18th des Julio. The two most delicious things of Montevideo are the climate & the flowers.” July 15th sees our party in Rio de Janeiro where they witness one of the many festivals complete with fireworks. After a brief visit the next stop is El Salvador where they visit the market, “a splendid spot for the study of niggerhood with all its farcical clothing, grimaces, antics & jokes.”

The journey across the tropics homeward is uneventful and on August 10th they arrive in Tenerife. “It was unspeakably joyful after 15 days incarceration to leap ashore on the pretty pier & ramble about the quiet, clean, sunny little town.” On the way back to England Essery lists, in true Victorian fashion, the achievements of their epic cruise around the world: “we stopped at 43 ports & we visited 34 inland cities & towns…I find further that we have seen 41 places not touched by Lady Brassey’s expedition…. I learn our whole cruise will measure 38,217 nautic miles.” With this great achievement, presented to the reader with a characteristic flourish, the redoubtable Reverend Essery brings to a close his journal, as epic in its scale as the journey he has both endured and at times enjoyed. The final sentence of the journal reflects his irrepressible good humour: “Our first business is to hurry on shore & flash by electricity to dear friends the message “Arrived, all well.””

Author

THE FIRST COMMERCIAL WORLD CRUISE.

Date

1881.

Publisher

Manuscript

Friends of the PBFA

For £10 get free entry to our fairs, updates from the PBFA and more.

Please email info@pbfa.org for more information