My Life with Stanley’s Rear Guard [from the library of Quentin Keynes]

Book Description

THE CLOTH-BOUND ISSUE OF AN ACCOUNT WRITTEN AT STANLEY’S SUGGESTION BY WARD, WHO WAS ‘HARSHER ON STANLEY THAN THE LATTER PROBABLY THOUGHT HE WOULD BE’

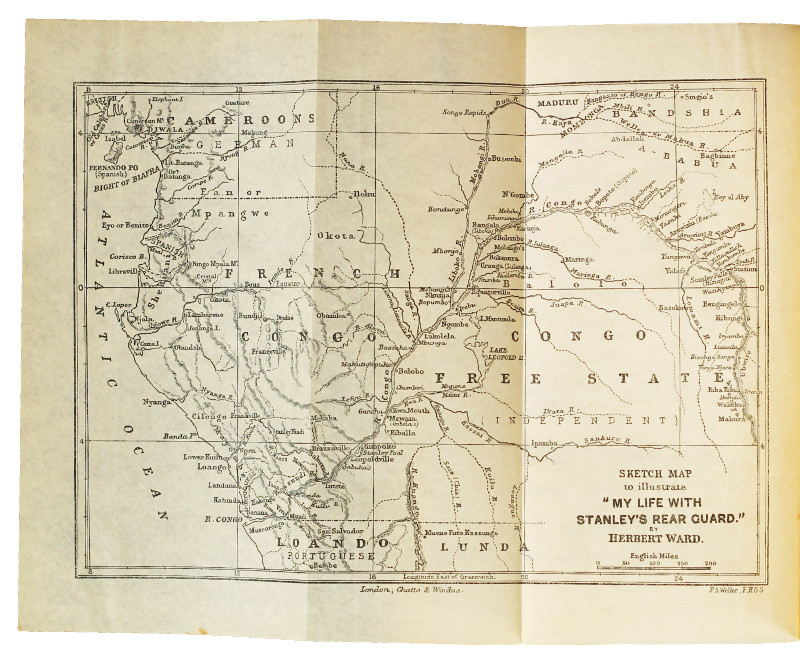

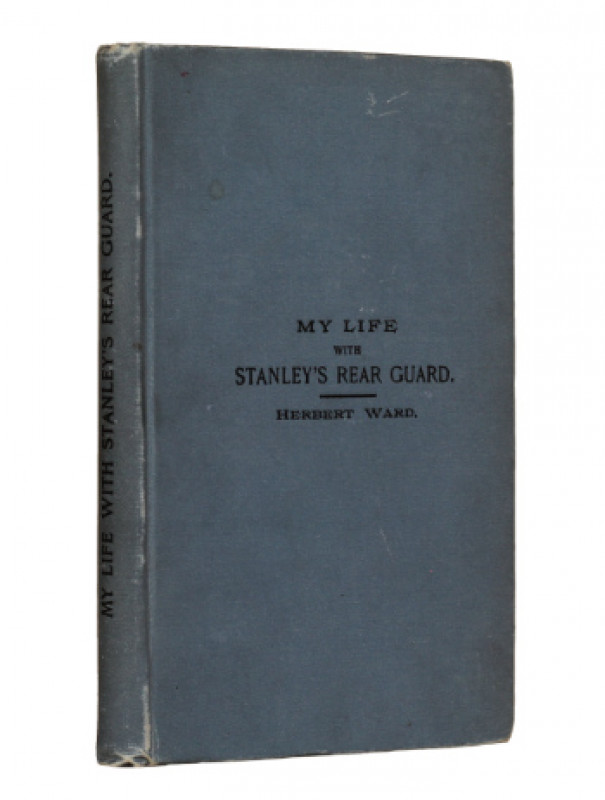

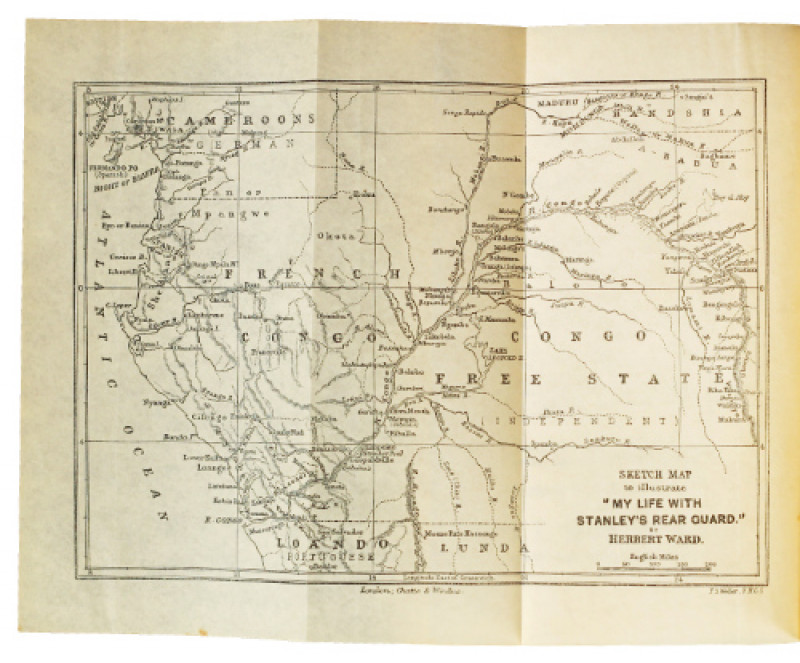

Octavo (184 x 125mm), pp. [i]-viii, 9-151, [1 (blank)]. One folding wood-engraved map after F.S. Weller. (A few light spots or marks.) Original blue-grey cloth, upper board and spine lettered in black, patterned endpapers, top edges stained grey. (A few light marks, extremities slightly rubbed and bumped.) A very good copy.

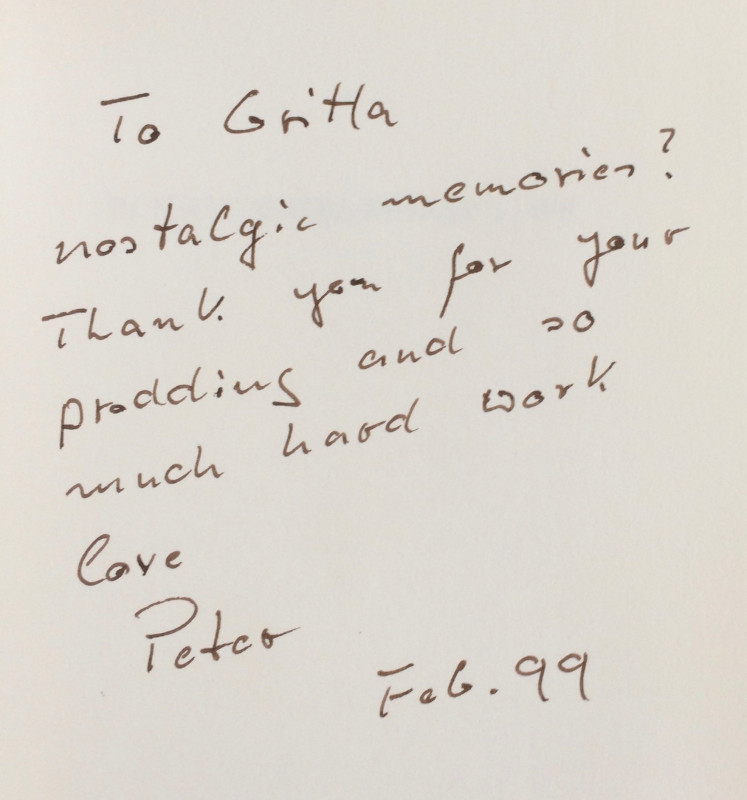

Provenance: Quentin George Keynes (1921-2003).

Octavo (184 x 125mm), pp. [i]-viii, 9-151, [1 (blank)]. One folding wood-engraved map after F.S. Weller. (A few light spots or marks.) Original blue-grey cloth, upper board and spine lettered in black, patterned endpapers, top edges stained grey. (A few light marks, extremities slightly rubbed and bumped.) A very good copy.

Provenance: Quentin George Keynes (1921-2003).

Dealer Notes

First American edition, cloth-bound issue. The traveller, writer, and artist Herbert Ward (1863-1919) left England for New Zealand as a teenager, and spent the following years travelling and working in New Zealand and Australia, before returning to England via the United States. He then went to Borneo in the employ of the British North Borneo Company, before a bout of malaria compelled him to travel to England to convalesce. In 1884, however, an interview with Henry Morton Stanley led to the offer of a position in the Congo working for the Manual Transport Agency, and Ward remained in the Congo for the following four years. Meanwhile, in London an expedition was being planned to relieve the German physician and scientist Eduard Schnitzer (known as Emin Pasha), the governor of Equatorial Sudan, who had been trapped by the Mahdist forces at Wadelai. Stanley was appointed by the committee of the Emin Pasha Relief Committee Expedition to lead the expedition, and he travelled to Africa in 1887. Ward heard of the expedition and Stanley’s arrival from a friend, who had also remarked on the difficulties of manning the expedition. Ward ‘soon gathered some three hundred of the required porters together, and, losing no time, set out with them to meet Stanley and his company’ (p. 11).

The party assembled by Ward soon encountered the expedition, and Stanley agreed that Ward and his group should join it. King Leopold of Belgium had promised Stanley the use of the boats of the Congo Free State, but when Stanley tried to deploy these boats he realised that damage and dilapidation had rendered them unusable, and that he needed to make other arrangements. Although he was able to procure other vessels, they did not provide sufficient capacity to transport the entire expedition, and ‘Stanley made a very difficult decision on 22 April 1887, which would come to haunt him for the rest of his life. He was still at Leopoldville when he noted in his diary that since he had too few steamers to take his entire party and its stores eastwards along the Upper Congo in one trip, he might have to split his expedition in two. He reasoned that if he were to set up a staging post at Yambuya, on the Aruwimi river, 1,100 miles to the east, he would be able to leave behind there a Rear Column of several hundred men to look after the bulk of his stores. Meanwhile, a smaller, unencumbered Advance Column would be freed to march eastwards at once from Yambuya to try to find Emin above Lake Albert. Unless this split was adopted, the march from Yambuya to Emin’s position would be delayed by two months [...]. If Emin Pasha should be overwhelmed in the meantime, the first question Stanley imagined being asked was why he had not split his expedition’ (T. Jeal, Stanley. The Impossible Life of Africa’s Greatest Explorer (London, 2007), p. 329).

Unfortunately, the Rear Column was plagued by illness, desertions, mismanagement, attacks, and disputes, and communications between the expedition’s two groups were intermittent or non-existent for much of the time they were separated. When Stanley, after successfully locating Emin Pasha, rejoined the Rear Column, he was horrified to learn from Sergeant Bonny, the medical assistant, how few of the original party survived. Indeed, Bonney’s report ‘constituted, said Stanley, “one of the most harrowing chapters of disastrous and fatal incidents that I ever heard attending the movements of an expedition in Africa”’ (op. cit., p. 353). Information about the terrible losses and the brutal behaviour of some officers and men in the Rear Column gradually became public knowledge, and recriminations followed, with different and contradictory accounts circulating widely. Ward, who had remained with the Rear Column, was one of the few officers to survive, and he explains in his introduction that in July 1890 ‘Mr. Stanley wrote to me privately, suggesting that I should write a little volume giving the story of my life with his Rear Guard. He further suggested that in this little book I should deal with the different matters in dispute between us. The proposal at the time had no charm for me. I wished to avoid controversy altogether, and to be allowed to forget, as far as possible, all about my connection with the Emin Expedition. The Rear Guard was a failure; something could undoubtedly be said on all sides of the question, and it seemed to me that, under all the circumstances, the subject had far better be left alone. [...] Much against my will, however, I have been dragged into the dispute; and, as there seems to be no help for it, I have decided to adopt Mr. Stanley’s old hint, and publish what I know of the Rear Guard. [...] When I decided to write this book, it appeared to me that the best plan would be to give a picture of life as it really was at Yambuya, avoiding all controversy in my narrative; and at the close to deal in a calm and impartial way with the different matters in dispute, as they affect myself. This is the course I have adopted’ (pp. vii-viii).

Casada comments that Ward was ‘harsher on Stanley than the latter probably thought he would be’, and notes that My Life with Stanley’s Rear Guard prints a number of letters from Stanley which were not included in Stanley’s In Darkest Africa when it appeared in 1890. My Life with Stanley’s Rear Guard was first published by Chatto and Windus in London in 1891 and was followed by this American edition later in the same year. Webster issued My Life with Stanley’s Rear Guard in two bindings: a cloth binding (as here, and also in brown cloth with gilt lettering) priced at $1.00, and a binding of printed wrappers, priced at 50 cents; presumably due to the difference in price, the copies in cloth bindings appear to be rarer on the market than those in wrappers.

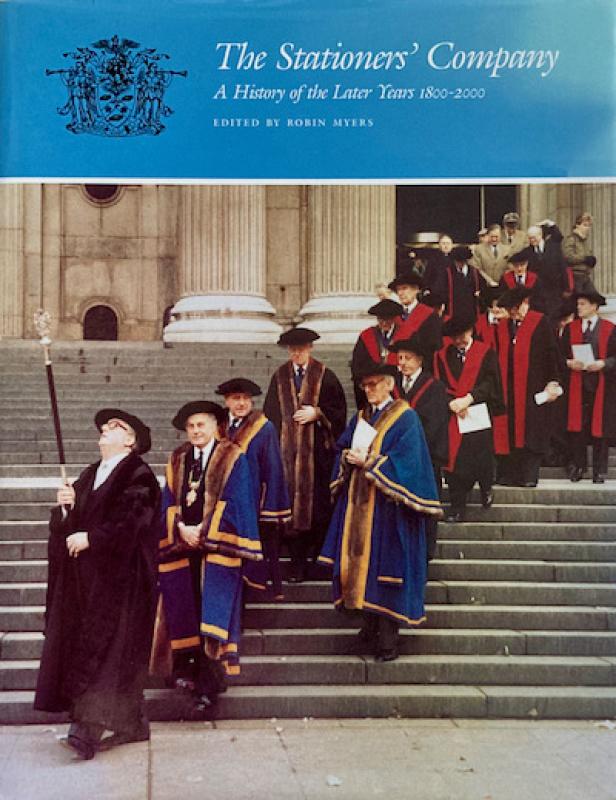

This copy was previously in the noted collection of the explorer and bibliophile Quentin Keynes, who travelled extensively in Africa throughout the second half of the twentieth century, and collected a remarkable library of books and manuscripts relating to the exploration of Africa, particularly during the nineteenth century. Some of these works provided the basis for Keynes’s Roxburghe Club book The Search for the Source of the Nile: Correspondence between Captain Richard Burton, Captain John Speke and Others, from Burton’s Unpublished East African Letter Book; together with Other Related Letters and Papers (London, 1999) and his collection was also a resource that he drew upon for his own travels in Africa. It was also a resource for writer and scholars studying Stanley and the history of African exploration, including Tim Jeal who used material from ‘Quentin Keynes’s unique African collection’ in his Stanley (p. 477).

Casada, Dr. David Livingstone and Sir Henry Morton Stanley, 1489.

* * *

This is one of the books from our recent Africa catalogue, which you may enjoy browsing. Catalogue available in our PBFA profile, or directly on www.typeandforme.com.

Please do not hesitate to contact us with any enquiries.

The party assembled by Ward soon encountered the expedition, and Stanley agreed that Ward and his group should join it. King Leopold of Belgium had promised Stanley the use of the boats of the Congo Free State, but when Stanley tried to deploy these boats he realised that damage and dilapidation had rendered them unusable, and that he needed to make other arrangements. Although he was able to procure other vessels, they did not provide sufficient capacity to transport the entire expedition, and ‘Stanley made a very difficult decision on 22 April 1887, which would come to haunt him for the rest of his life. He was still at Leopoldville when he noted in his diary that since he had too few steamers to take his entire party and its stores eastwards along the Upper Congo in one trip, he might have to split his expedition in two. He reasoned that if he were to set up a staging post at Yambuya, on the Aruwimi river, 1,100 miles to the east, he would be able to leave behind there a Rear Column of several hundred men to look after the bulk of his stores. Meanwhile, a smaller, unencumbered Advance Column would be freed to march eastwards at once from Yambuya to try to find Emin above Lake Albert. Unless this split was adopted, the march from Yambuya to Emin’s position would be delayed by two months [...]. If Emin Pasha should be overwhelmed in the meantime, the first question Stanley imagined being asked was why he had not split his expedition’ (T. Jeal, Stanley. The Impossible Life of Africa’s Greatest Explorer (London, 2007), p. 329).

Unfortunately, the Rear Column was plagued by illness, desertions, mismanagement, attacks, and disputes, and communications between the expedition’s two groups were intermittent or non-existent for much of the time they were separated. When Stanley, after successfully locating Emin Pasha, rejoined the Rear Column, he was horrified to learn from Sergeant Bonny, the medical assistant, how few of the original party survived. Indeed, Bonney’s report ‘constituted, said Stanley, “one of the most harrowing chapters of disastrous and fatal incidents that I ever heard attending the movements of an expedition in Africa”’ (op. cit., p. 353). Information about the terrible losses and the brutal behaviour of some officers and men in the Rear Column gradually became public knowledge, and recriminations followed, with different and contradictory accounts circulating widely. Ward, who had remained with the Rear Column, was one of the few officers to survive, and he explains in his introduction that in July 1890 ‘Mr. Stanley wrote to me privately, suggesting that I should write a little volume giving the story of my life with his Rear Guard. He further suggested that in this little book I should deal with the different matters in dispute between us. The proposal at the time had no charm for me. I wished to avoid controversy altogether, and to be allowed to forget, as far as possible, all about my connection with the Emin Expedition. The Rear Guard was a failure; something could undoubtedly be said on all sides of the question, and it seemed to me that, under all the circumstances, the subject had far better be left alone. [...] Much against my will, however, I have been dragged into the dispute; and, as there seems to be no help for it, I have decided to adopt Mr. Stanley’s old hint, and publish what I know of the Rear Guard. [...] When I decided to write this book, it appeared to me that the best plan would be to give a picture of life as it really was at Yambuya, avoiding all controversy in my narrative; and at the close to deal in a calm and impartial way with the different matters in dispute, as they affect myself. This is the course I have adopted’ (pp. vii-viii).

Casada comments that Ward was ‘harsher on Stanley than the latter probably thought he would be’, and notes that My Life with Stanley’s Rear Guard prints a number of letters from Stanley which were not included in Stanley’s In Darkest Africa when it appeared in 1890. My Life with Stanley’s Rear Guard was first published by Chatto and Windus in London in 1891 and was followed by this American edition later in the same year. Webster issued My Life with Stanley’s Rear Guard in two bindings: a cloth binding (as here, and also in brown cloth with gilt lettering) priced at $1.00, and a binding of printed wrappers, priced at 50 cents; presumably due to the difference in price, the copies in cloth bindings appear to be rarer on the market than those in wrappers.

This copy was previously in the noted collection of the explorer and bibliophile Quentin Keynes, who travelled extensively in Africa throughout the second half of the twentieth century, and collected a remarkable library of books and manuscripts relating to the exploration of Africa, particularly during the nineteenth century. Some of these works provided the basis for Keynes’s Roxburghe Club book The Search for the Source of the Nile: Correspondence between Captain Richard Burton, Captain John Speke and Others, from Burton’s Unpublished East African Letter Book; together with Other Related Letters and Papers (London, 1999) and his collection was also a resource that he drew upon for his own travels in Africa. It was also a resource for writer and scholars studying Stanley and the history of African exploration, including Tim Jeal who used material from ‘Quentin Keynes’s unique African collection’ in his Stanley (p. 477).

Casada, Dr. David Livingstone and Sir Henry Morton Stanley, 1489.

* * *

This is one of the books from our recent Africa catalogue, which you may enjoy browsing. Catalogue available in our PBFA profile, or directly on www.typeandforme.com.

Please do not hesitate to contact us with any enquiries.

Author

WARD, Herbert

Date

1891

Publisher

New York: Jenkins & McCowan for Charles L. Webster & Company

Friends of the PBFA

For £10 get free entry to our fairs, updates from the PBFA and more.

Please email info@pbfa.org for more information