Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah. Edited by Thomas L. Wolley [from the library of Stephen Keynes]

Book Description

BURTON’S ACCOUNT OF HIS HAJ – A CLASSIC OF TRAVEL LITERATURE, WHICH ‘SURPASS[ED] ALL PRECEDING WESTERN ACCOUNTS OF THE HOLY CITIES’

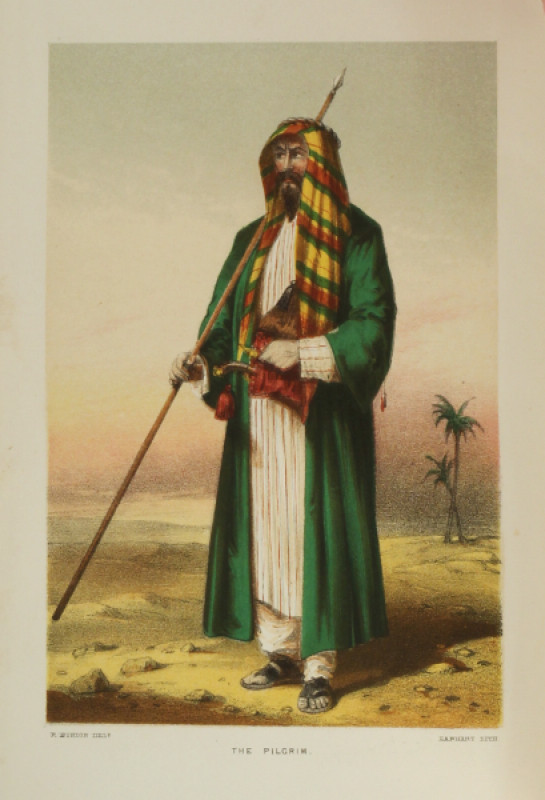

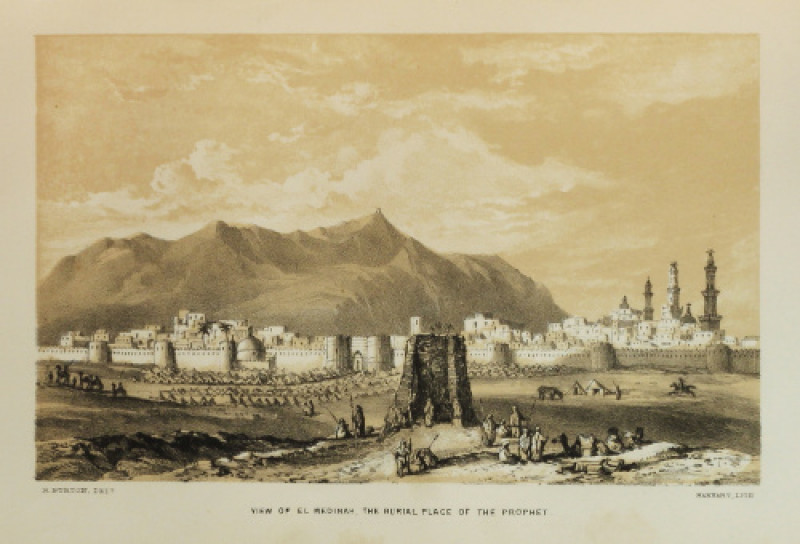

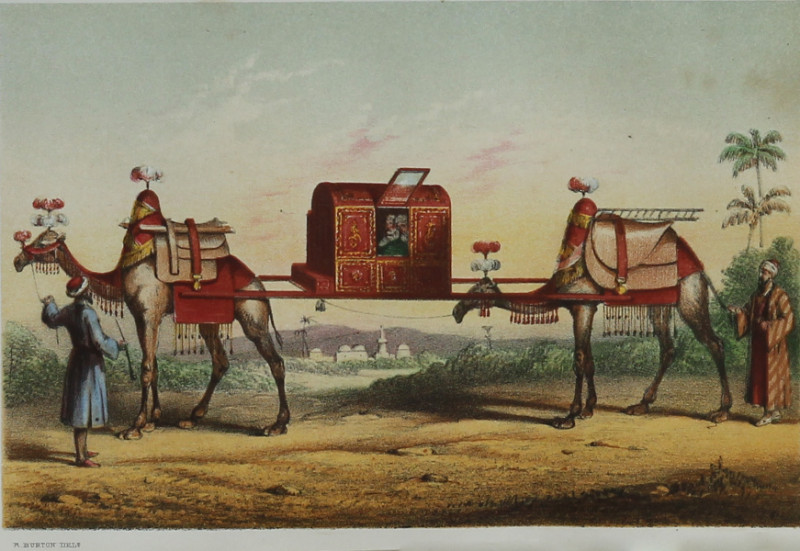

3 volumes, octavo (223 x 140mm), pp. I: [i]-xiv, [2 (errata, verso blank)], [1]-388, [1]-24 (publisher’s advertisements printed by Wilson and Ogilvy, dated September 1854); II: [i]-iv, [1]-326; III: [i]-x, [2 (list of plates, verso blank)], [1]-448, [1]-24 (publisher’s advertisements printed by Wilson and Ogilvy, dated November 1854). Printed in Roman and Arabic types. Tinted lithographic frontispiece (I) and colour-printed lithographic frontispieces (II-III) by Hanhart after Burton (I-II) and J. Brandard (III), those in I and II retaining tissue guards. 3 colour-printed lithographic plates by Hanhart after Burton and Brandard, and 7 tinted lithographic plate by Hanhart after Burton, all retaining tissue guards, one wood-engraved plate, 3 folding engraved maps and plans by E. Weller and J. Adlard after E. Weller, and one wood-engraved plan. Wood-engraved illustrations in the text. (Some light spotting and offsetting, occasional light marking, some quires clumsily opened causing marginal tears and occasional losses.) Original blue cloth by Edmonds and Remnants, London with their ticket on the lower pastedowns of vols I and III, boards blocked in black with broad decorative borders, spines blocked with designs in black and lettered in gilt, terracotta pastedowns with printed advertisements on pastedowns, uncut, modern blue cloth slipcase. (A few light marks, extremities somewhat rubbed and bumped, skilfully rebacked, retaining original spines, vol. I book block cracked in quire A.) A very good, internally clean set in the original cloth, retaining the half-title in vol. III and the publisher’s catalogues in vols I and III.

Provenance: Stephen John Keynes OBE, FLS (1927-2017).

3 volumes, octavo (223 x 140mm), pp. I: [i]-xiv, [2 (errata, verso blank)], [1]-388, [1]-24 (publisher’s advertisements printed by Wilson and Ogilvy, dated September 1854); II: [i]-iv, [1]-326; III: [i]-x, [2 (list of plates, verso blank)], [1]-448, [1]-24 (publisher’s advertisements printed by Wilson and Ogilvy, dated November 1854). Printed in Roman and Arabic types. Tinted lithographic frontispiece (I) and colour-printed lithographic frontispieces (II-III) by Hanhart after Burton (I-II) and J. Brandard (III), those in I and II retaining tissue guards. 3 colour-printed lithographic plates by Hanhart after Burton and Brandard, and 7 tinted lithographic plate by Hanhart after Burton, all retaining tissue guards, one wood-engraved plate, 3 folding engraved maps and plans by E. Weller and J. Adlard after E. Weller, and one wood-engraved plan. Wood-engraved illustrations in the text. (Some light spotting and offsetting, occasional light marking, some quires clumsily opened causing marginal tears and occasional losses.) Original blue cloth by Edmonds and Remnants, London with their ticket on the lower pastedowns of vols I and III, boards blocked in black with broad decorative borders, spines blocked with designs in black and lettered in gilt, terracotta pastedowns with printed advertisements on pastedowns, uncut, modern blue cloth slipcase. (A few light marks, extremities somewhat rubbed and bumped, skilfully rebacked, retaining original spines, vol. I book block cracked in quire A.) A very good, internally clean set in the original cloth, retaining the half-title in vol. III and the publisher’s catalogues in vols I and III.

Provenance: Stephen John Keynes OBE, FLS (1927-2017).

Dealer Notes

First edition. Following his rustication in 1842 after an unauthorised visit to a steeplechase, the explorer and author Richard Burton (1821-1890) left Oxford for a commission in the Honourable East India Company’s Bombay Army. He arrived in India on 28 October 1842 and (in addition to his duties as an infantry officer), worked variously as a surveyor, intelligence officer, and interpreter, achieving particular distinction as a linguist: Burton’s ‘phenomenal gift for mastering languages, apparent from childhood, flowered in India as he periodically exhibited proficiency in the East India Company’s language examinations. Within a year of his arrival, he had scored first in both the Hindustani and Gujarati examinations, administered under the strict supervision of the accomplished orientalist Major-General Vans Kennedy. Altogether Burton passed seven language examinations in India; over the course of his lifetime, he mastered more than forty languages and dialects’ (ODNB).

This ability to assimilate languages and cultures rapidly and comprehensively stood him in good stead when he was gathering intelligence in disguise, but a bout of cholera (and the hostility of some of his military colleagues) led to Burton’s return to England on sick leave in 1849. In the following years Burton wrote four books based on his experiences in the Bombay Army: Goa and the Blue Mountains (London, 1851); the semi-autobiographical Scinde, or, The Unhappy Valley (London, 1851); Sindh, and the Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus (London, 1851), which is ‘still widely regarded as the best textbook on many aspects of Scindi ethnology’ (M. Lovell, A Rage to Live. A Biography of Richard and Isabel Burton (London, 1999), p. 109); and Falconry in the Valley of the Indus (London, 1852).

In England Burton also learnt that the Royal Geographical Society had a fund of £200 available for an expedition to Arabia, which had never been drawn upon by its intended beneficiaries, and proposed that he use it to join ‘the Egyptian caravan for Cairo, and to penetrate via Medinah and Meccah, through the province of Hadramaut to the southern coast of Arabia’ (op. cit., p. 118). This was approved, and with ‘support from the Royal Geographical Society and a leave from the East India Company, Burton sailed from England in April 1853. Burton first travelled to Egypt, where he spent a month in Alexandria and some further weeks in Cairo renewing his familiarity with Islamic mannerisms. He modified his former persona [of Mirza Abdullah of Bushehr, half Arab and half Iranian, under which disguise he had previously travelled,] to become Sheikh Abdullah, a wandering Sufi dervish and practitioner of medicine. So successful was he in the latter role that he soon developed a thriving practice. He also perfected his Arabic, which he had learned in India, at [the] venerable al-Azhar University. After the fasting month of Ramadan he proceeded by camel to Suez, whence a tumultuous voyage on a pilgrim boat took him to the Arabian port of Yanbu’ al-Bahr. He then travelled by caravan to Medina, arriving on 25 July 1853. There he remained for some weeks as he explored the city, visiting the Prophet’s tomb and venturing to nearby sites such as the battlefield at Uhud. On 31 August he departed Medina with the Damascus caravan and reached Mecca early on 11 September 1853. Later that morning he proceeded to the Great Mosque and stood before the Kaaba’ (ODNB).

Burton described his arrival thus: ‘[t]here at last it lay, the bourn of my long and weary pilgrimage, realising the plans and hopes of many and many a year. The mirage medium of Fancy invested the huge catafalque and its gloomy pall with peculiar charms. There were no giant fragments of hoar antiquity as in Egypt, no remains of graceful and harmonious beauty as in Greece and Italy, no barbarous gorgeousness as in the buildings of India; yet the view was strange, unique – and how few have looked upon the celebrated shrine! I may truly say that, of all the worshippers who clung weeping to the curtain, or who pressed their beating hearts to the stone, none felt for the moment a deeper emotion than did the Haji from the far north. It was as if the poetical legends of the Arab spoke truth, and that the waving wings of angels, not the sweet breeze of morning, were agitating and swelling the black covering of the shrine. But, to confess humbling truth, theirs was the high feeling of religious enthusiasm, mine was the ecstasy of gratified pride’ (III, pp. 199-200). Burton was also one of the small number of pilgrims who were raised up to the entrance of the Kaabah, more than two metres above the ground, in order to enter the holiest place in Mecca.

In the following week, Burton undertook the rites that formed part of the pilgrimage, circumambulating the Kaaba, drinking the Zemzem water, and stoning the devil at Mount Arafat, which entitled him to call himself Hajji and to wear a green turban. Throughout, ‘he secretly made the detailed notes that enabled his resulting book to surpass all preceding Western accounts of the holy cities. Burton had originally hoped to continue east into the unexplored regions of central Arabia, but unrest among the Bedouin tribes prevented him, so he returned to Egypt in the early autumn of 1853’ (ODNB).

Much of the Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah was written while Burton was abroad and the book was seen through the presses by Thomas L. Wolley, who provided a preface in which he explained that the original plan to publish the three volumes together was frustrated by the delayed arrival of the manuscript of the third volume from India. Therefore, the first two volumes were published together in 1855 and the last volume in 1856. The work ‘made Burton famous and became a classic of travel literature’ (ODNB), and – as Penzer wrote in 1923 – it is ‘[v]ery rare’ (p. 50).

This set is from the library of the noted bibliophile Stephen Keynes, a great-grandson of Charles Darwin, the founder and chairman of the Charles Darwin Trust. Stephen Keynes was a member of the Roxburghe Club, as was his older brother Quentin Keynes, who was a noted collector of Burton’s works and presented The Search for the Source of the Nile: Correspondence between Captain Richard Burton, Captain John Speke and Others, from Burton's Unpublished East African Letter Book: together with Other Related Letters and Papers to the Club in 1999.

Casada 53 (‘the best known of a Burton’s original works’); Gay 3634; Ibrahim-Hilmy I, p. 111; Kalfatovic 0462; Penzer, pp. 49-50.

This ability to assimilate languages and cultures rapidly and comprehensively stood him in good stead when he was gathering intelligence in disguise, but a bout of cholera (and the hostility of some of his military colleagues) led to Burton’s return to England on sick leave in 1849. In the following years Burton wrote four books based on his experiences in the Bombay Army: Goa and the Blue Mountains (London, 1851); the semi-autobiographical Scinde, or, The Unhappy Valley (London, 1851); Sindh, and the Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus (London, 1851), which is ‘still widely regarded as the best textbook on many aspects of Scindi ethnology’ (M. Lovell, A Rage to Live. A Biography of Richard and Isabel Burton (London, 1999), p. 109); and Falconry in the Valley of the Indus (London, 1852).

In England Burton also learnt that the Royal Geographical Society had a fund of £200 available for an expedition to Arabia, which had never been drawn upon by its intended beneficiaries, and proposed that he use it to join ‘the Egyptian caravan for Cairo, and to penetrate via Medinah and Meccah, through the province of Hadramaut to the southern coast of Arabia’ (op. cit., p. 118). This was approved, and with ‘support from the Royal Geographical Society and a leave from the East India Company, Burton sailed from England in April 1853. Burton first travelled to Egypt, where he spent a month in Alexandria and some further weeks in Cairo renewing his familiarity with Islamic mannerisms. He modified his former persona [of Mirza Abdullah of Bushehr, half Arab and half Iranian, under which disguise he had previously travelled,] to become Sheikh Abdullah, a wandering Sufi dervish and practitioner of medicine. So successful was he in the latter role that he soon developed a thriving practice. He also perfected his Arabic, which he had learned in India, at [the] venerable al-Azhar University. After the fasting month of Ramadan he proceeded by camel to Suez, whence a tumultuous voyage on a pilgrim boat took him to the Arabian port of Yanbu’ al-Bahr. He then travelled by caravan to Medina, arriving on 25 July 1853. There he remained for some weeks as he explored the city, visiting the Prophet’s tomb and venturing to nearby sites such as the battlefield at Uhud. On 31 August he departed Medina with the Damascus caravan and reached Mecca early on 11 September 1853. Later that morning he proceeded to the Great Mosque and stood before the Kaaba’ (ODNB).

Burton described his arrival thus: ‘[t]here at last it lay, the bourn of my long and weary pilgrimage, realising the plans and hopes of many and many a year. The mirage medium of Fancy invested the huge catafalque and its gloomy pall with peculiar charms. There were no giant fragments of hoar antiquity as in Egypt, no remains of graceful and harmonious beauty as in Greece and Italy, no barbarous gorgeousness as in the buildings of India; yet the view was strange, unique – and how few have looked upon the celebrated shrine! I may truly say that, of all the worshippers who clung weeping to the curtain, or who pressed their beating hearts to the stone, none felt for the moment a deeper emotion than did the Haji from the far north. It was as if the poetical legends of the Arab spoke truth, and that the waving wings of angels, not the sweet breeze of morning, were agitating and swelling the black covering of the shrine. But, to confess humbling truth, theirs was the high feeling of religious enthusiasm, mine was the ecstasy of gratified pride’ (III, pp. 199-200). Burton was also one of the small number of pilgrims who were raised up to the entrance of the Kaabah, more than two metres above the ground, in order to enter the holiest place in Mecca.

In the following week, Burton undertook the rites that formed part of the pilgrimage, circumambulating the Kaaba, drinking the Zemzem water, and stoning the devil at Mount Arafat, which entitled him to call himself Hajji and to wear a green turban. Throughout, ‘he secretly made the detailed notes that enabled his resulting book to surpass all preceding Western accounts of the holy cities. Burton had originally hoped to continue east into the unexplored regions of central Arabia, but unrest among the Bedouin tribes prevented him, so he returned to Egypt in the early autumn of 1853’ (ODNB).

Much of the Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah was written while Burton was abroad and the book was seen through the presses by Thomas L. Wolley, who provided a preface in which he explained that the original plan to publish the three volumes together was frustrated by the delayed arrival of the manuscript of the third volume from India. Therefore, the first two volumes were published together in 1855 and the last volume in 1856. The work ‘made Burton famous and became a classic of travel literature’ (ODNB), and – as Penzer wrote in 1923 – it is ‘[v]ery rare’ (p. 50).

This set is from the library of the noted bibliophile Stephen Keynes, a great-grandson of Charles Darwin, the founder and chairman of the Charles Darwin Trust. Stephen Keynes was a member of the Roxburghe Club, as was his older brother Quentin Keynes, who was a noted collector of Burton’s works and presented The Search for the Source of the Nile: Correspondence between Captain Richard Burton, Captain John Speke and Others, from Burton's Unpublished East African Letter Book: together with Other Related Letters and Papers to the Club in 1999.

Casada 53 (‘the best known of a Burton’s original works’); Gay 3634; Ibrahim-Hilmy I, p. 111; Kalfatovic 0462; Penzer, pp. 49-50.

Author

BURTON, Sir Richard Francis

Date

1855-1856

Publisher

London: A. and G.A. Spottiswoode (I-II) and Spottiswoode & Co. (III) for Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans

Friends of the PBFA

For £10 get free entry to our fairs, updates from the PBFA and more.

Please email info@pbfa.org for more information